The recent announcement that Theranos CEO Elizabeth Holmes has been banned from the blood-testing industry for two years is the latest chapter in the company’s rise and fall, a cautionary tale in what can happen when media hype and millions of dollars in investment funds collide with the revolutionary but untested claims of a driven, dynamic founder.

Until Theranos came under scrutiny from federal regulators, much of the laudatory press coverage focused on the company’s origin story—the turtleneck-clad Stanford dropout who idolized Steve Jobs and wanted to change the world through technology. Holmes landed on the covers of Fortune, Forbes, Inc. and T: The New York Times Style Magazine, and the New Yorker and Wired published lengthy profiles. At its peak, Theranos was valued at $9 billion, making Holmes the youngest self-made female billionaire in the world, at the helm of an enterprise whose board was packed with luminaries including Henry Kissinger and former Secretary of State George Shultz.

Holmes claimed her company had developed a process that would upend American medicine by allowing dozens of laboratory tests to be run off a few drops of blood at a fraction of the cost of traditional methods. But whether its technology actually works is still an open question, as Holmes has never allowed it to be examined by outside researchers, nor its data to be peer-reviewed. Last fall, the Wall Street Journal reported that Theranos’s proprietary Edison machines were inaccurate and it had been running tests on the same equipment used by established labs such as Quest Diagnostics and Laboratory Corporation of America. This set in motion a spate of bad news for the startup: investigations by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Securities and Exchange Commission and U.S. Department of Justice; the cancellation of an agreement with Walgreens to open blood-testing centers in pharmacies nationwide; the voiding of two years of Theranos blood results; and class-action lawsuits from consumers who say their health was compromised by faulty data. (For an excellent summary of the company’s rise and fall, check out this graphic from NPR.)

The excitement over Theranos was based on its claim of proprietary technology that, if real, had the potential to revolutionize lab testing and the healthcare decisions that are based on it. But at the core of its vision was a less sensational though equally central premise: that direct-to-consumer blood testing is the future of American healthcare. As Holmes put it in a 2014 TEDMED talk, enabling consumers to test themselves for diseases before showing any symptoms would “redefine the paradigm of diagnosis.” By determining their risk for a condition before developing it, people could begin treatment at an earlier stage. Take, for example, Type 2 diabetes, which Holmes says drives 20 percent of our healthcare costs and can be reversed through lifestyle changes: 80 million Americans have a condition called prediabetes, and most of them don’t know because it generally produces no symptoms—no headache, no muscle pains, no nausea or fever or chills—and is detectable only through a blood test.

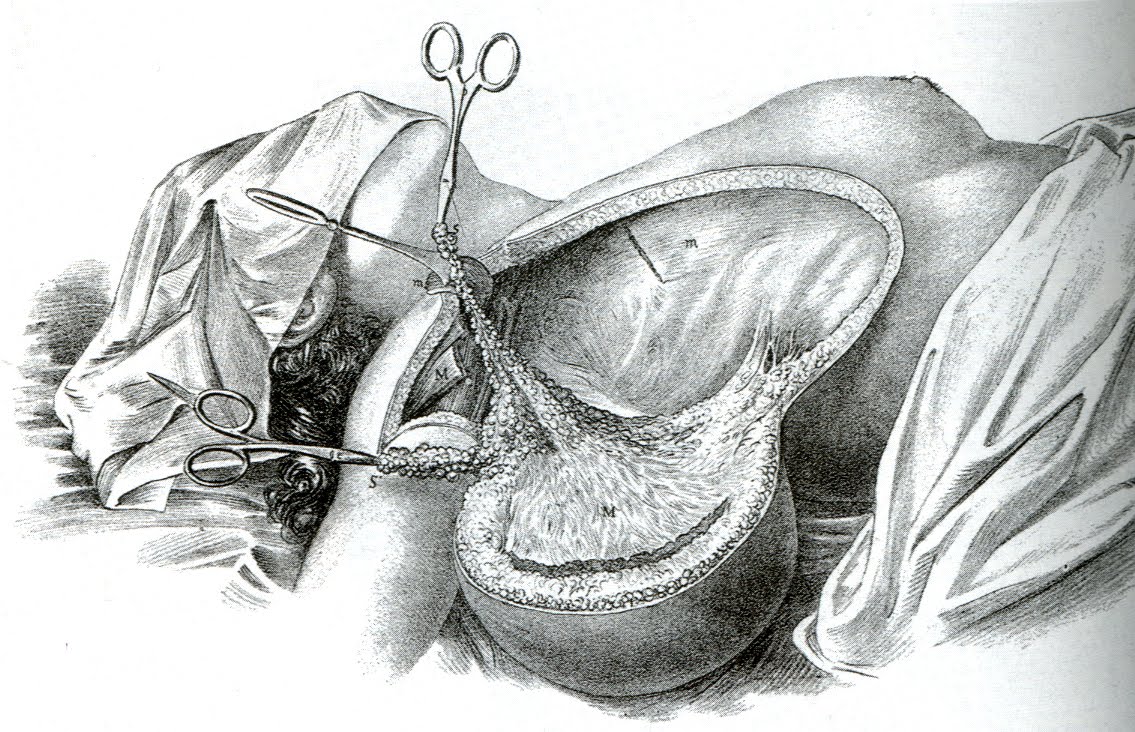

The removal of the subjective experiences of the patient from the act of diagnosis has been a part of medical practice since the mid-1800s, when the modern stethoscope made it possible to observe the internal workings of the body in a non-invasive way. By the beginning of the twentieth century, an assortment of new instruments gave doctors access to technical information that patients could neither see nor interpret. The laryngoscope and electrocardiograph offered data independent of an individual’s perceptions, while a new device to measure blood pressure found its place in the doctor’s medical bag. Hemocytometers and hemoglobinometers enabled microscopic examination of the size and number of blood cells, allowing hematologists, as these specialists became known, to read the blood and manipulate it to treat various disorders. Together, these instruments reduced the physician’s reliance on a patient’s subjective description of symptoms in favor of precise, quantifiable data.

As diagnostic technologies have grown more sophisticated, a number of symptomless conditions have appeared that didn’t previously exist. Many of these are defined by deviation from a numerical threshold: high blood pressure, for instance, or prediabetes. But as physician and historian Jeremy A. Greene has written, these numbers can change due to shifting medical opinion or adjustment by pharmaceutical companies, which have an incentive to make the population of patients who are candidates for their drugs as large as possible. When the American Diabetes Association lowered the threshold for prediabetes in 2003, the population of prediabetics instantaneously expanded. No one’s health changed that quickly, just our definition of which patients had a condition and who should take medication for it.

The assumptions underlying a medicine-by-numbers approach are that disease is detectable with diagnostic instruments before the onset of experiential symptoms, and more data is always better. Our blood does contain an immense amount of crucial information about our well-being, from levels of vitamin D and electrolytes to the presence of bacteria and antibodies. But as the history of blood testing shows, the idea of blood as an infallible roadmap to one’s health, a substance that with the proper analysis will inevitably reveal incipient disease, has not always held up. More data is not always more useful, especially if we lack the tools to understand it or if the medical meaning of the information is in flux. Three separate readings of the CA 15-3 biomarker for breast cancer may look nearly identical to a physician, writes Eleftherios P. Diamandis of the University of Toronto, but in a patient could prompt a range of reactions from anxiety to jubilation, depending on where the numbers fall as predictors of cancer recurrence.

Defining diseases solely by numerical thresholds invites the possibility that these numbers could be manipulated, and with them the boundary between health and disease. Today’s normal cholesterol might be tomorrow’s borderline hyperlipidemia. Numbers-based medicine may hold enormous appeal in its apparent ability to translate the opacity of blood into quantifiable data, but treating every out-of-range figure as a marker of proto-disease is no guarantee that we’ll end up any healthier. We may just end up with more information.

Sources:

Eleftherios P. Diamandis, “Theranos Phenomenon: Promises and Fallacies.” Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine 53, 7 (June 2015).

Jeremy A. Greene, Prescribing By Numbers: Drugs and the Definition of Disease. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Keith Wailoo, Drawing Blood: Technology and Disease Identity in Twentieth-Century America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.